By Brett Walton

A National Research Council report argues that groundwater use today is leaving society poorly prepared for potential rapid climate changes in the future.

It is no exaggeration to claim that aquifers—water-saturated layers of subterranean sediment—have allowed agriculture, and thus modern life in our house of seven billion, to prosper.

America’s Great Plains are a lucrative grain bin solely because of the Ogallala Aquifer, which waters eight states. In New Mexico, groundwater reserves helped farmers survive the recent drought in the Southwest. The key to India’s Green Revolution, which pulled hundreds of millions out of hunger starting in the 1960s, was millions of wells irrigating land sown with new types of seeds.

These examples are twentieth and early twenty-first century success stories. But a new report from the National Research Council claims that these patterns of water use, if not recast, leave society vulnerable to climate surprises.

Surprises, in this context, are not felicitous. They are disruptive and destructive. They are the result of too much carbon in the atmosphere and the oceans and a warming of the global climate. They are changes in the rate of change, rapid upheavals that can overwhelm the rural and the urban, the coasts and the heartlands.

Published Dec. 3, Abrupt Impacts of Climate Change assesses the potential for these large-scale “tipping points” and whether they are expected sooner or later.

The good news is that the direst circumstances—a belch of heat-trapping methane from thawing polar soils or a seizure in the ocean’s heat conveyor belt, which would affect rainfall, temperature, sea level and marine ecosystems—are not expected to occur this century.

A rapid melting of the West Antarctic ice sheet, which would raise sea levels by at least three meters (10 feet) if it completely melted, was judged plausible by 2100 but with a low probability and high uncertainty.

The more likely disruptions are the ones that are familiar: heat waves, extinctions, droughts and floods. They are “more likely, severe and imminent,” according to the report. Their effects will be amplified by how society manages its resources and builds its infrastructure.

“Groundwater aquifers, for example, are being depleted in many parts of the world, including the southeast of the U.S.,” the report states. “Groundwater is critical for farmers to ride out droughts, and if that safety net reaches an abrupt end, the impact of droughts on the food supply will be even larger.”

When rain is scarce, farmers turn on the pumps. But in most key agricultural regions, more water is being taken out than filters back in. In money terms, farmers are blowing through their savings account, leaving little in the bank if an expensive bill comes due.

To be fair, groundwater regulations have popped up with increasing frequency in states such as Arizona, Kansas and Nebraska and many cities are storing more water underground, but spendthrifts still outnumber mattress-stuffers.

Caution Signs Needed

In light of this, the report’s authors—all U.S. professors that study the Earth, air and oceans—argue for an advance warning system for abrupt changes, a flashing yellow semaphore to jar society out of an all-systems-go complacency.

An Abrupt Change Early Warning System, they write, would require three activities:

identification of vulnerable areas that are then monitored frequently to detect changes

development of models that can predict changes

incorporation of new knowledge and analysis

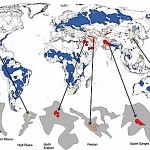

Regarding monitoring, the report calls out for special attention NASA’s GRACE satellite mission, which measures changes in the Earth’s water resources by detecting changes in gravitational pull between two satellites.

When coupled with climate forecasts, continuous global groundwater assessments could anticipate failed harvests and poor crop production.

“A successful ACEWS that monitors for food security should include such monitoring, as groundwater withdrawal is the common approach to combating the impact of drought on crop yields. A failure of groundwater to backstop rain would be a tipping point in the production of food, and a central part of a system to forecast famine.”

Some small regional or topical warning systems exist—the report mentions America’s National Integrated Drought Information System and the Famine Early Warning System in East Africa and the Sahel—but big global schemes will take time, the authors acknowledge.

Best to begin now.

Visit EcoWatch’s WATER page for more related news on this topic.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.