By Emily Atkin

On Sunday night, a reporter for The Weather Channel stood in a Minnesota snowstorm, talking about local efforts to move homeless children into heated shelters. “How cold is it supposed to get?” the anchor, back in the studio, asked.

The reporter replied: “Colder than Mars.”

Indeed, recent temperatures across the U.S. have been Mars-like. Forecasts in the midwest call for temperatures to drop to 32 below zero in Fargo, ND, minus 21 in Madison, WI, and 15 below zero in Minneapolis, Indianapolis and Chicago. Wind chills have been predicted to fall to negative 60 degrees—a dangerous cold that could break decades-old records.

All of which begs the question—if climate change is real, then how did it get so cold?

The question is based on common misconceptions of how cold weather moves across the planet, said Greg Laden, a bioanthroplogist who writes for National Geographic’s Scienceblog. According to Laden, the recent record-cold temperatures indicate to many that the Arctic’s cold air is expanding, engulfing other countries. If true, this would be a perfect argument for a “global cooling” theory. The Arctic’s coldness is growing. Laden asks, “How can such a thing happen with global warming?”

The answer, he writes, is that the Arctic air that usually sits on top of our planet is “taking an excursion” south for a couple of days, leaving the North Pole “relatively warm” and our temperate region not-so-temperate. “Go Home Arctic, You’re Drunk,” he titled the explanation.

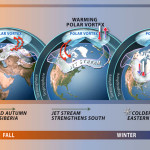

“The Polar Vortex, a huge system of moving swirling air that normally contains the polar cold air, has shifted so it is not sitting right on the pole as it usually does,” Laden writes. “We are not seeing an expansion of cold, an ice age, or an anti-global warming phenomenon. We are seeing the usual cold polar air taking an excursion. So, this cold weather we are having does not disprove global warming.”

In fact, some scientists have theorized that the influx of extreme cold is actually fueled by effects of climate change. Jennifer Francis, a research professor at Rutgers University’s Institute of Marine and Coastal Science, told ClimateProgress on Monday that it’s not the Arctic who is drunk. It’s the jet stream.

“The drunk part is that the jet stream is in this wavy pattern, like a drunk walking along,” Francis, who primarily studies Arctic links to global weather patterns, said. “In other places, you could see the tropics are drunk.”

Arctic warming, she said, is causing less drastic changes in temperatures between northern and southern climates, leading to weakened west-to-east winds, and ultimately, a wavier jet stream. The stream’s recent “waviness” has been taking coldness down to the temperate U.S. and leaving Alaska and the Arctic relatively warm, Francis said. The same thing has been happening in other countries as well. Winter storms have been pounding the UK, she noted, while Scandinavia is having a very warm winter.

“This kind of pattern is going to be more likely, and has been more likely,” she said. “Extremes on both ends are a symptom. Wild, unusual temperatures of both sides, both warmer and colder.”

Francis’ research, however, is still disputed. Dr. Kevin E. Trenberth, a distinguished senior climate scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, told ClimateProgress on Monday that he was skeptical of Francis’ assessment.

“Jennifer’s work shows a correlation, but correlation is not causation,” he cautioned. “In fact it is much more likely to work the other way around.”

Instead of Francis’ theory that a warm Arctic moves the jet stream, Trenberth said it could be that the jet stream moves, leading to a warmer Arctic. And Francis’ theory could work if the Arctic was, in fact, particularly warm and iceless—at the moment, in winter, the Arctic is cooler and icier.

“I am not saying there is no [climate change] influence, but in midwinter, the energy in these big storms is huge and the climate change influence is impossible to find statistically,” he said. “So we have to fall back on understanding the processes and mechanisms.”

Still, Trenberth—based in Boulder, CO,—just had 11 inches of snow on Saturday, which he said is the third largest ever for the month. Normally the area gets only light, fluffy snow. But, he said temperatures on Friday were 62 degrees, making for extra moisture and heat, “probably” contributing to the extra snow. The incident mimics what Trenberth’s research has shown—that increased moisture and heat from climate change has an effect on weather events.

“The answer to the oft-asked question of whether an event is caused by climate change is that it is the wrong question,” he has written. “All weather events are affected by climate change because the environment in which they occur is warmer and moister than it used to be.”

Visit EcoWatch’s CLIMATE CHANGE page for more related news on this topic.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.