By Max Macpherson, PVEL, and Alex Barrows, Exawatt/CRU Group

With the waiver of AD/CVD circumvention tariffs on SE Asian cells and modules that employ Chinese wafers set to expire in June this year, there are several key issues for the U.S. solar market. One of these is for the courts to decide on — Auxin’s recent lawsuit against U.S. Customs and the Department of Commerce, arguing that the application of the tariff waiver itself was unlawful. If Auxin gets its way, the imposition of retroactive tariffs on modules already imported could lead to major costs and yet more uncertainty, with reviews of tariff rates and subsequent appeals dragging on for years.

Aside from the arguments about the validity of the tariff waiver, another key question is how easily module suppliers can sidestep the duties (in much the same way that SE Asian manufacturing was established at scale in large part to sidestep the original imposition of AD/CVD on Chinese cells and modules).

There are several options to sidestep AD/CVD duties. For example:

- Manufacturing cells and modules in SE Asia using wafers from countries other than China.

- Manufacturing modules in SE Asia using Chinese wafers but with sufficient non-Chinese input materials.

- Manufacturing modules in a third country using SE Asian cells which employ Chinese wafers.

- Manufacturing cells and modules (and, optionally, wafers) in the U.S.

Wafers – a simple solution, but hard to source

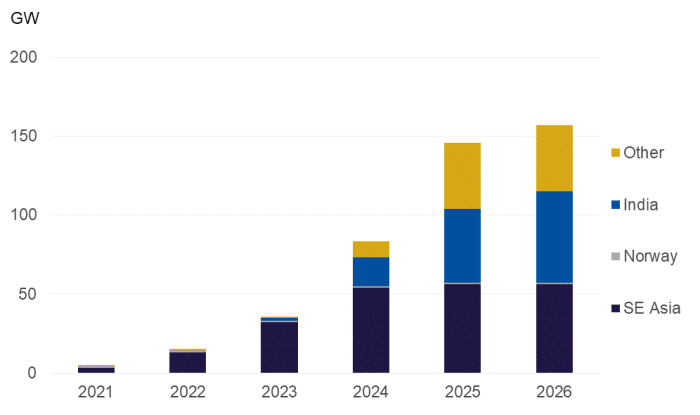

Perhaps the most obvious option to enable imports from SE Asia (of both cells and modules) without paying AD/CVD duties is to use wafers sourced from outside of China. Wafer capacity outside of China is increasing rapidly, and for many of the larger vertically-integrated manufacturers this solution will remove the tariff risk — Jinko, LONGi, Trina and JA Solar all have meaningful wafer manufacturing capacity in SE Asia, while Canadian Solar, Runergy and Elite Solar are planning capacity in the near future.

However, SE Asian wafer capacity is largely set to be part of a vertically integrated manufacturing strategy in the region, and the bulk of other wafer expansion plans outside of China are also part of a strategy of vertical integration. The availability of third-party wafers is likely to remain very limited, leaving manufacturers without their own in-house capacity looking for an alternative solution.

Module materials

If, as we expect, there is a shortage of non-China wafers available commercially in the near term and medium term, manufacturers may opt to avoid AD/CVD duties on their SE Asian modules by replacing their current dependence on Chinese components. Duties will only apply to SE Asian modules that are manufactured with both a Chinese wafer and three or more Chinese input materials from the list of six (glass, frame, silver paste, backsheet, EVA, junction box).

For PV glass, we believe that there was ~80 GW of PV glass capacity outside of China by the end of 2023, growing to ~95 GW by the end of 2024. Key suppliers include Flat Glass (Vietnam) and Xinyi (Vietnam and Malaysia) — also the two largest suppliers of PV glass in China — as well as Borosil (India). Some of this capacity is already used to serve Indian module manufacturers due to Indian anti-dumping tariffs on Chinese PV glass. Assuming U.S. module demand of 40-50 GW in 2025 and Indian demand of ~15-20 GW in 2025, the volume of non-China PV glass should be sufficient to serve these markets over the next few years (even ignoring the high volume of module production that will not require non-China materials due to the use of a non-China wafer).

Frames have been less immediately available than glass, although extrusion capacity should not be a major issue in the medium term and by the end of 2023 we believe that approximately 20-30 GW of frame manufacturing capacity was in operation in SE Asia.

For silver paste, we believe that access to non-China silver paste is not currently likely to be a major bottleneck, and supply should be sufficient for SE Asian cell manufacturing. The requirements for backsheets and EVA depend heavily on module architecture choices and technology choices. However, broadly we believe that encapsulation supply may be sufficient, especially when considering that POE from China — commonly used as an alternative to EVA in dual-glass modules — does not appear to be covered by the circumvention determination.

Overall, it appears that the supply of non-China input materials should be sufficient to allow SE Asian module manufacturers to sidestep module tariffs via this option where they cannot source a non-China wafer. However, this will come with an associated cost increase and a limited surplus of supply for some materials will leave limited room to maneuver in the event of any unexpected supply-chain disruptions. In addition, it is not clear at exactly what point manufacturers have adjusted supply chains — making it very difficult to know what proportion of recent module imports might be at risk of retroactive tariffs if Auxin is successful in its lawsuit.

Alternative manufacturing locations

Manufacturing modules in a third country using cells from SE Asia based on wafers from China is also an option for some manufacturers to avoid AD/CVD. Here India, Turkey and Korea all have meaningful module capacity outside the circumvention ruling, and some specific manufactures already have module manufacturing in other locations that would enable this (e.g., Maxeon’s module capacity in Mexico).

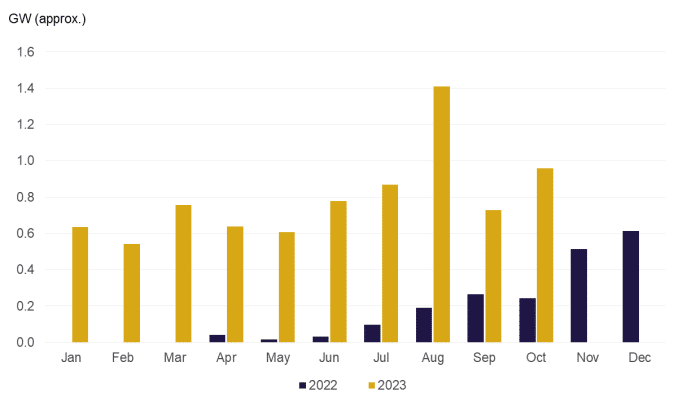

Indeed, Indian module exports have grown rapidly since early 2022 and are almost all targeted at the U.S., which accounted for >98% of the country’s module exports during the first 10 months of 2023.

Ironically, module manufacturers in the U.S. that are reliant on third-party cells may find themselves in the most challenging position. The use of non-Chinese module materials cannot be used as a sidestep for duties when importing only the cell, and cell manufacturing capacity in third countries is far more limited that module manufacturing capacity, making finding suppliers in alternative countries more challenging. Factor in the limited commercially available supply of non-China wafers, and the challenges in rapidly bringing cell capacity online in the U.S., and this looks to be the most challenging area for avoiding tariffs during the next couple of years.

Quality impacts

Regarding the question of how drastically each of these elements could impact the final product if it is different from the previous bill of materials (BOM), in PVEL’s Product Qualification Program (PQP) testing, there are certain components and elements that will trigger a retest if what was in the original BOM is changed (changes in materials defined by IEC TS 62915:2018). For the non-wafer products mentioned in the ruling:

- Glass. If the front glass is changed, it triggers a retest for any test involving the integrity of the glass, such as mechanical stress, hail, PID, or IAM (and UVID if the glass thickness changes). Glass cracks can lead to corrosion and safety issues. Rear glass changes would trigger the same retests as a backsheet change.

- Frame. If the frame changes, it triggers a retest for tests related to mechanical stress. Improper frame design can lead to mechanical failure and/or cell damage.

- Silver paste. Not specifically something that triggers a retest.

- Backsheet. If the backsheet is changed, it will trigger a retesting for multiple reliability tests, and if a backsheet is swapped out for back glass or vice versa, it triggers an entirely new PQP. Cracked backsheets or rear-side glass can lead to delamination, corrosion, and/or safety concerns.

- EVA. If the encapsulant is changed, it triggers a retest on almost all PQP tests. Degradation can result in discoloration, delamination and/or corrosion.

- Junction box. If the junction box is changed, it will trigger a DH retest. Junction box failure can lead to corrosion and/or electrical arcing and fire.

Lab testing has shown drastic differences in performance between the exact same BOM with even one change of material. If manufacturers need to change suppliers for module materials due to the circumvention ruling, we would expect to see a change in quality that would need to be tested.

Conclusion

Overall, we believe that most modules imported into the U.S. will be able to sidestep the extension of the AD/CVD duties. However, this will come with some challenges to logistics and supply-chain management, will push up some costs, will lead adjustments in quality for some non-China components, and could in particular have implications for quality and reliability if any changes in BOM are not handled carefully. Ironically, it seems likely that module manufacturers in the U.S. that are reliant on purchasing cells from SE Asian suppliers may find themselves in the most challenging position when it comes to avoiding tariffs.

Max Macpherson is Data and Analytics Reports Manager at PVEL, and Alex Barrows, Head of PV at Exawatt/CRU Group.

— Solar Builder magazine

[source: https://solarbuildermag.com/news/likelihood-of-solar-modules-avoiding-ad-cvd-tariffs/]

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.