This is an article from the Q2 2023 edition of Solar Builder magazine, written by Christian Roselund, senior policy analyst at Clean Energy Associates.

The passage of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) was a groundbreaking moment for how the United States addresses the climate crisis, but it is having an even more profound effect by launching the United States’ first comprehensive clean energy industrial policy.

By addressing the higher costs of U.S. manufacturing through Section 45x tax incentives, the IRA tackles a major barrier to “on-shoring” the U.S. solar supply chain. In doing so, the new law is stimulating investment in a massive volume of solar module factories.

While there is excitement around all the new factory announcements, there is a more complex and nuanced situation on the ground. When looking at manufacturing the components that go into these modules — polysilicon, ingot, wafer and cell factories — the announced investments in domestic U.S. capacity are far more limited. Of course, it remains to be seen whether any given factory that has been announced will arrive on the timelines planned. Any delays and cancellations of projects will mean less capacity than announced.

Investments along the value chain

The incentives in the IRA are not the first time the United States has tried to boost the domestic solar supply chain.

Despite two rounds of anti-dumping and countervailing duties (AD/CVD), against China in 2012, and China and Taiwan in 2014, U.S. solar factories continued to close. And while some new manufacturing came in the wake of the Section 201 tariffs in 2018, this was limited to module factories, and domestic module capacity additions continued to lag demand. Concurrently, the last U.S. ingot, wafer and crystalline silicon cell factories closed.

A central challenge has been that manufacturing costs — including operating costs such as labor and utilities — are simply higher in the United States. By incentivizing production instead of investment in factories, the Section 45x incentives provide the first U.S. federal incentives to directly offset these higher operating costs.

Nonetheless, Section 45x comes to an industry that has already largely moved overseas, with the remaining domestic operations highly dependent on imported inputs. At its most basic level, the absence of U.S. cell factories means that even domestic crystalline silicon module makers must import cells, and the absence of ingot and wafer factories means that U.S. polysilicon cannot be processed into wafers domestically.

Most cells imported into the United States come from Southeast Asia or South Korea. The ingots and wafers that they use largely come from China. Despite more factories coming online in Southeast Asia, China still holds 96% of global ingot and wafer capacity.

For the United States to reach a fully integrated domestic supply chain, these industries must be rebuilt from scratch. A critical part of building competitive ingot, wafer and cell factories is having personnel who understand the latest technologies and how to work with them. Staff with this know-how will have to be brought in. Building U.S. ingot and wafer factories may also involve importing tools from Asia, which may be limited if China finalizes its proposed export controls on large-format wafer technologies.

Ongoing import dependence

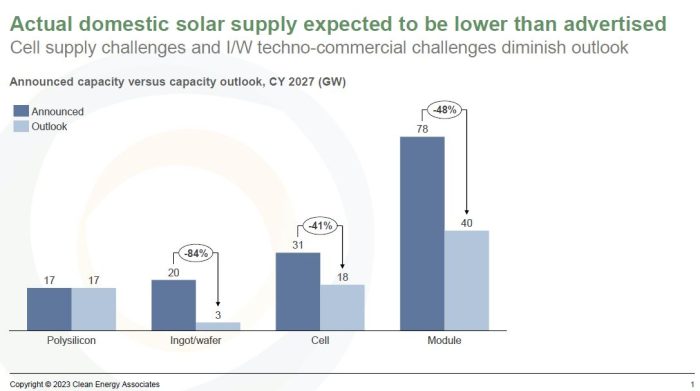

Clean Energy Associates has identified substantial announcements along the solar value chain, with existing and announced new module factories planned to account for 78 GW in 2027 — a roughly 7-fold increase over today’s capacities. However, not all of that will be built, and not all of it will be built on time.

When we discount those figures to what we think is likely to be completed, we expect more like 40 GW of U.S. module capacity in 2027. That would be 7 GW less than the 47 GW of installations we are projecting for 2027. This indicates that even if all U.S. production were to run at full capacity, and all the modules produced were used domestically, the United States would still need to import PV modules.

For other parts of the value chain, the differences are starker.

- Of the 31 GW of announced and existing cell capacity (counting First Solar’s integrated thin-film production), we expect only 18 GW to be online in 2027.

- For ingot and wafer, CEA is projecting a mere 3 GW in 2027.

- And there are no announcements for polysilicon manufacturing beyond the pending restart of the REC Silicon facility in Washington, leaving the United States lacking with only 17 GW of polysilicon capacity.

This uneven state of both announcements and expected capacity along the solar value chain so far means that even in a best-case scenario, the United States is likely to remain partly dependent on solar imports. It also means that a shortage of cells available for import could limit the production of U.S.-made PV modules, at least until more factories come online.

For ingots and wafers, the United States is likely to remain dependent on imports for the vast majority of modules deployed in the United States.

Looking to the future

U.S. domestic manufacturing capacities are a moving target. CEA expects more U.S. cell manufacturing to be announced following the Treasury’s publication of guidance for the Domestic Content adder to the Investment Tax Credit and the Production Tax Credit. We do not expect much more domestic ingot, wafer or polysilicon capacity to be announced, leaving U.S. factories dependent on imports for these areas of the supply chain

As the U.S. solar market continues its path of growth, imports from other nations such as India will become more important. However, India also lags in upstream supply, with limited cell capacity and no ingot, wafer or polysilicon production at present.

Additional U.S. policies could emerge to support manufacturing, which could be critical at the polysilicon, ingot and wafer levels. While IRA incentives are generous, one central challenge to date has been that these incentives begin to phase out in 2030 and are gone in 2033. Given the 3 to 5 years needed to build and ramp ingot, wafer and polysilicon production, this leaves relatively little time to get such plants online and claim the incentives.

Extension of the Section 45x incentives beyond 2030 — even if only for ingot, wafer, and polysilicon — could be one way to address this problem.

The United States must still grapple with the challenge that the practical know-how to build and operate state-of-the-art ingot and wafer facilities is concentrated in Asia and particularly in Chinese companies. This creates a potent additional challenge to building ingot and wafer and may require some flexibility in policy if the United States wants to build a domestic industry.

The United States is onshoring solar in a powerful way, but comprehensive, robust manufacturing ecosystems are not built in a day, or even a year. A deeper onshoring of U.S. manufacturing beyond module production is going to require time, flexibility and patience.

Keep reading …

For more exclusive expert insight from Solar Builder magazine, access the digital edition right here.

— Solar Builder magazine

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.